Reviewing 'Blackbird - How Black musicians sang The Beatles into being-and sang back to them ever after' by Katie Kapurch and Jon Marc Smith (2023), part 1

Ray Charles in Newport 1958.

NEWPORT 19581

‘I Got a Woman’ begins tender, then dances, and soon runs into a great rocking performance. ‘Talkin’ About You’ has a great drive. ‘The Right Time’ is happy and not yet a screamer, but it could be. The call-and-response exchange with the choir is bluesy. It gets me rocking at the keyboard. Who is that soulful screaming/singing woman at the end? She could have been the inspiration for Paul McCartney's screaming like Little Richard.

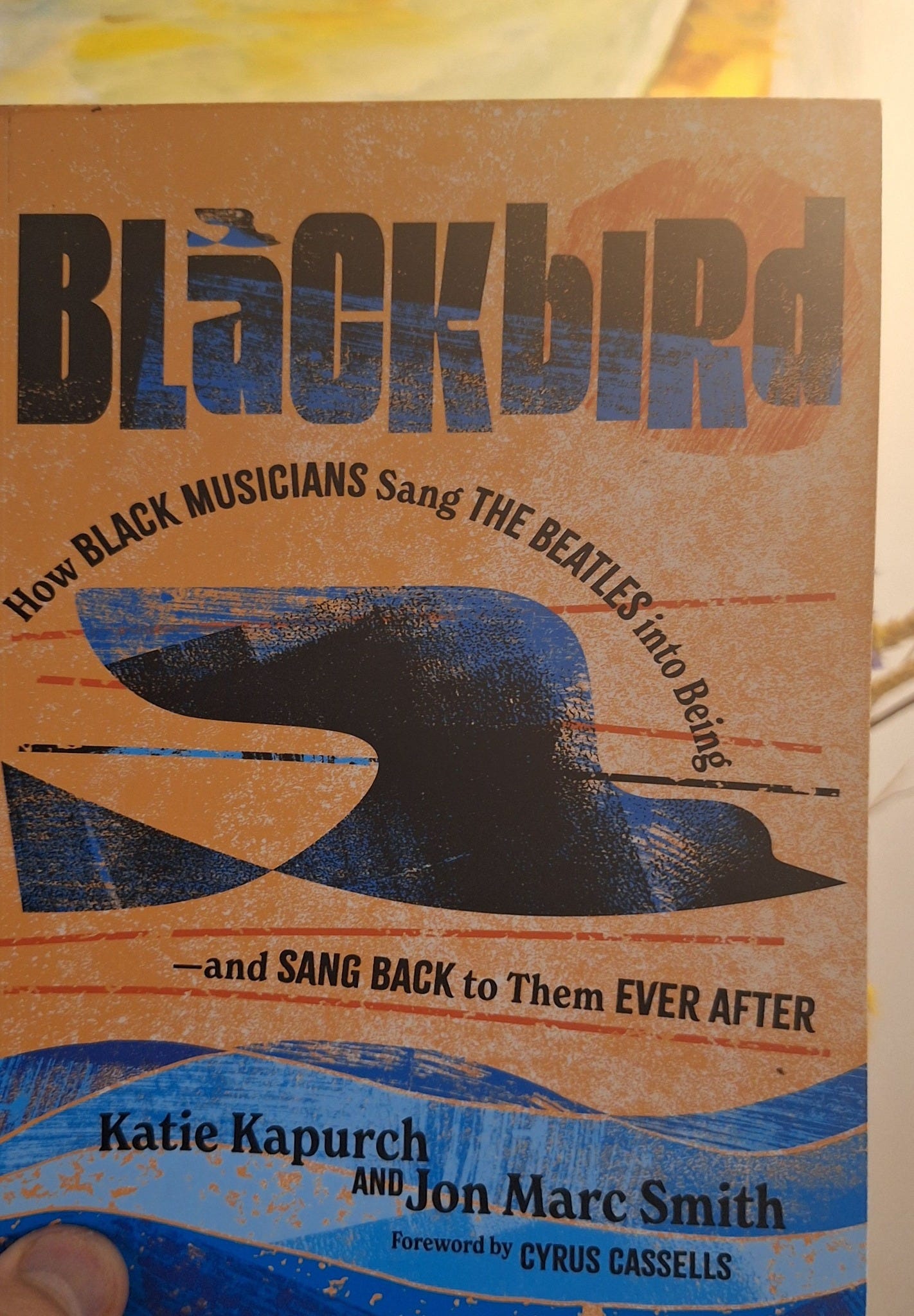

While sitting at my desk writing, I can hardly stay put and keep my mouth shut. I want to hear more from Ray Charles. My heart and gut are hungry for soul music, it is interfering with the task I set myself to do. I am trying to scan and then read ‘Blackbird’ (2023)2. Hope it is a masterpiece.3 A study of The Beatles’ song ‘Blackbird’(1968)4, by academics Katie Kapurch5 and Jon Marc Smith6. They seem to be a good team working at Texas State University. A few years ago Katie noticed that she and her partner in crime, Jon March Smith, “talk, I believe, all day long”.7

Kapurch’s work on The Beatles is expansive, arresting, and outstanding. A list of ± 30 (since 2014) publications from my files is in Appendix 1. If you study The Beatles regularly, you’ve probably read her work more than once. She is capable of researching and telling mind-bending stories.

I hope this text has the potential to change our understanding of the song ‘Blackbird’. I study to find a new edge, or balance, between knowing enough to know I am right, and not knowing enough to know I am wrong.

The question is which part of ‘Blackbird’ is under review? What will the authors explore, interpret, and explain: the composition, the creation, or the listener’s understanding and perception? The way to observe art is to discern

[a] What triggers or inspires the creation of the song?

b) The creation phase, including the artist’s intention and the craftsmanship required to produce the work.

c) The realm of the audience. When a work of art is finished and made available to the audience, the creator loses control and ownership. We, the people, determine what the song means. The art evokes our emotions, or maybe nothing at all.

Conflating the artist’s intention, creative impulses, and historiographical development is a curse. Critics and fans who think about ‘all things Beatles’, and even academics, are guilty of this. The amalgamation of the creation and intention of art and the critical or public reception is almost impossible to avoid in American academic culture, especially with an iconic popular cultural phenomenon.

Journalists and the marketing power of his Beatles legacy trigger Paul McCartney to talk too much. He makes things up, for whatever reason. But so does every artist or celebrity. As an entertainer and keeper of the legacy, McCartney often steps into the limelight, free and friendly, with the critical but still fawning fans and uninformed journalists being unresponsive or hostile. Too often the ensuing confusion is about too much of nothing.

In discussing a popular work of art or entertainment, it is helpful to distinguish between A) the work of art, and separate inspiration, intention, and creation; B) how the audience and the media perceive or communicate, and represent this work of art (that would be popular culture); and C) how the art might inspire other artists and the results of this inspiration (that would be in the realm of the history of art).

The complete title of the book gives you the gist of the authors’ aim :

‘Blackbird – How black musicians sang The Beatles into being—and sang back to them ever after.’

Exploring music by black artists requires understanding where they are coming from. To know and understand their metaphors in storytelling and musical stylistic options. Inevitably Kapurch and Smith will cover the suffering still going on ages after slavery was abolished, but institutionalized discrimination and race-based disenfranchisement are still rampant. Sadly whities use this racist attitude as part of the ‘normal’ political conversation, e.g. the racism in the political campaigns by the GOP is obvious and intentional.

The text discusses great artists who inspired The Beatles’ music and how they got inspired by The Beatles. From my perspective, The Beatles’ historiography shows a loaded relationship with the Black community. Only a few fans of color were among the young fans visiting concerts in the 60s. Motown stars were inspiring life, love, and sex, not the music of The Beatles. Uncritical fans and Apple Corp amplify the meaning of the anti-segregation stand by The Beatles during the 1964 tour into mythical unreal proportions. Even though Sly Stone had warned us, whities, not to call him nigger8, John and Yoko used the N-word in their politically driven ‘Woman in the Nigger of the World’ (1972). It subsequently undermined the effectiveness of the tune, the album, and themselves.9 This reveals limited worldviews, and smacks of political and artistic naivety and laziness, which is demanded as an artistic impulse makes use of politically driven associations or messages.

I hope Kapurch and Smith will change my perspective on the racial relations in The Beatles narrative.

I got to get up and dance, and sing.

After two months of waiting for the book, the urge to get into it is as strong as the spur to move and feel the music of Ray Charles. I need to make a choice. I love ‘Mess Around’. Ray Charles swings, I remember listening for weeks to the full box set ‘The Birth of Soul’ (1991) in the 1990s.

I don’t waste time, so I sing and dance to Ray Charles music while I do the household chores, up the stairs, down the hall, into the garden, cleaning the windows while I am fooling around. Perhaps I look like Freddy Mercury in the video clip for ‘I Want to Break Free’.10 I move and sing as if I perform for a small audience. Next, I feel like I am singing to the thousands in a large auditorium or a stadium, in the end, I am back in my room, singing to my lover, who sits cross-legged across the carpet. I click on ‘Got A Woman’, again, and then ‘What I’d Say’, and then and then and then. I have stopped reading the Blackbird book as I click on ‘The Long and Winding Road’ and ‘Eleanor Rigby’. I cannot stop listening. Singing along with Ray Charles, with his inflections and intonation make my cheeks get wet. My singing voice may not be strong and clear, but as tears flow, I guess, I must be doing well. The Beatles’ renditions of these songs do not have this effect on me. The performance of Ray Charles on ‘The Long and Winding Road’ triggers goosebumps. This man croons, he aches, and moves. Ray Charles can be jubilant too. He has a superb feel for melody, sound and rhythm.

I have no idea which songs from Ray Charles The Beatles covered. They performed ‘I Got a Woman’ on the BBC in ‘Pop Go The Beatles’, on August 13, 1963. Listen to Lennon’s rhythm guitar part, this is pure Beatles music, wild, driving, and enchanting.11 For ‘I Feel Fine’ they used the rhythm of ‘What I’d Say’ as inspiration for the drum part. The Beatles accompany Billy Preston when he starts a little jam on the piano with ‘Sticks on Stones’, on January 28th, 1969 at Savile Row.12

Listening to a lot of music, I return to the book. I discover Katie and Jon Marc seem infatuated by the bird metaphor: “(Billy) Preston’s presence in The Beatles as well as in their (solo works), spans the past, present, and future like a bird flying across times and places”.13

In the foreword Cyrus Cassells shows that the use of this metaphor is not casual:

an “absorbing fascinating musical and cultural history” based on the authors’ “diligent research” and documentation show that “in the visions of the formerly trammeled people, the still-moving and emoting blackbird remains a perennial figure of hope and liberation. The ubiquity of birds, especially black ones, in arts of the African diaspora goes back centuries. That tradition never died, ...”

I look forward to Kapurch and Smith exploring this background and hope to learn from it.

The continuing story of Paul McCartney and ‘Blackbird’

I have my observations about ‘Blackbird’. There is no indication that McCartney used the ‘bird’ metaphor in the sense of African American folktales. McCartney acknowledged he was thinking about a black woman, and was aware of the existential problems she would be confronted with. This is similar to the imagery that inspired ‘Lady Madonna’. The principal part in ‘Another Day’, is for a woman in a similar situation, a non-racial woman, who suffers from boredom and loveless loneliness. She writes to a radio show to talk about her problems and asks a panel to discuss resolutions for the predicaments in her life—the dark side of working-class and bourgeois life, common for so many lonely people. Consumerism, booze, depression, drugs, psychological devastation, or suicide are the range of sad outcomes for her.

In ‘Blackbird’ McCartney chooses the phrase ‘a bird’ for an individual woman, which works better than “Black woman living in Little Rock”, as he explained to Barry Miles in ‘Many Years from Now’.14 When fans and critics increasingly asked about the meaning of the songs, and Paul, after being stifled by Lennon’s public vengeance, realized that “audiences really appreciate finding an angle into the planetary atmosphere of the song, by getting to see the far side of the moon” he told Paul Muldoon for his ‘Paul McCartney – The Lyrics’ (2021).15 Indeed any personal lyric with a ‘universal’ appeal works well with the audience.

In the late 1990s Adrian Mitchell, poet, and at the time editor of ‘Blackbird Singing’ (2001)16, explained to Paul “if you can think of any interesting anecdote about the poem (during a poetry reading), that’s always a good lead-in.” This became the concept for ‘The Lyrics’ book and the podcast ‘McCartney: A Life in Lyrics’17. Paul tweaks his story about ‘Blackbird’ for entertainment purposes.

Nina Simone wrote her ‘Blackbird’ in 1963. It is a first-person account of being in a miserable situation, and she sings about resignation. Why ‘rise’ or ‘fly away’? It has no use. When I was 12, in 1968/9 I learned about Nina Simone through her hit ‘Ain’t Got No, I Got Life’ on pirate Radio Veronica, which in my memory still sounds like “Ain’t got no home, Ain’t got no life”. It is musically reminiscent of Clarence ‘Frogman’ Carter. Thematically it is related to Woody Guthrie’s ‘Ain’t got no home, I’m just a roamin’ round’. Simone is not quiet about the deplorable state of herself and the black community. When I was young her performances of her own ‘Revolution’, and renditions of ‘Here Comes the Sun’, and ‘Isn’t it a Pity’ triggered wider interest, and I discovered her among the elpees my father had. Nina Simone had composed a reaction to ‘Revolution’. John mentioned this in 1970 but he avoided the conversation or had no clue what Nina Simone was singing about.18

The covers of ‘Blackbird’ I knew

McCartney’s song and the Blackbird metaphor burn brightly when performed by black artists who express soul.

Sylvester’s 1979 live version on the album ‘Living Proof’19 makes

Blackbird fly

Into the light

Of a dark black night

the most meaningful part. Inciting to fly is key for Sylvester and his soulful backing singers, not the empathetic poetic flourishes of Paul’s lyrics. Sylvester’s arrangement was rhythmic and melodically unlike Paul’s folksy original. This taught me how the song could be taken differently. It took over two decades before the discussion about whether people believed Paul’s stage chatter about the Civil Rights Movement happened. Paul’s lyrics are not about any political movement. He sings about individual people, about family.

In 2011, Bettye LaVette gave an amazing rendition of ‘Blackbird’ in The Jazz Café in London20. It is a beautiful but painful first-person interpretation. LaVette makes the song completely about herself. Most of her repertoire refers to herself, as you can discover in her biography, ‘A Woman Like Me’ (2012).20 The book is an enchanting story that makes you cringe and laugh.

I took my broken wings and learned how to fly

I took my sunken eyes and taught my own self how to see

All of my life

I have waited for this moment to arise

I have waited and waited and waited

For this moment to be free

In 2020 LaVette turns ‘Blackbird’ into a song about the ‘Blackbirds’, the female artists who sang rhythm and blues in the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s.21 She made the story personal again, in support of the Black women who suffer because of their descent. They need a chance to fly into the dead of the night, to be free from all that shit.

Beyoncé is the latest artist to cover ‘Blackbird’. My judgment is out. Maybe I need to learn to hear the inflections. Rob Sheffield seems to hear. In a Rolling Stone article about Beyoncé’s ‘Blackbird’,22 he merges dreams and reality in superb fandom entertainment. On closer reading, I noticed Sheffield offers too many lines ‘copy-paste-edit’ from his ‘Dreaming The Beatles’ book (2017)23. It’s click-bait. The focus on forever re-hashed stuff like in many nostalgia-oriented music publications24 is a betrayal of qualitative music criticism.

And in the end,

it doesn’t matter what McCartney’s intentions were. Listeners should open up, let the song move them, and then feel and think. What matters is what does it mean to you. It is the audience's and other artists’ privilege to take the song and morph its meaning into whatever they/we/he/she/you and me, want or need. That is the fate of art. Thirty years after Thomas Mann finished ‘Der Zauberberg’, he acknowledged:

“It's barely mine anymore. It has become detached from me and has a life of its own.”

Another seventy years later, in a dark theater room, a black cube, ‘der Kulturplatz’, everybody’s talking about their own Magic Mountain. Outside the nicest summer weather, they sit inside trying to piece together the novel and its meaning a century after publication. The author is the last person they would ask. One academic calls the work an anti-nationalist novel. Another speaks of a parody of the ‘bildungsroman’. The Magic Mountain is a time and space novel, that investigates and puts these concepts into perspective. The androgynous protagonist Clawdia Chauchat seduces the other protagonist Hans Castopr over hundreds of pages without uttering a word. This fuels the gender discussion in a contemporary way, according to the academics present; for was she a woman or a man, or neither?

Sorry Paul, you may lean back and count the beans, while we take your song and round with the experience, with our dilemmas, pain, and joy.

.

In the ‘foreword’ of the book, Cassells claims, that savvy artists detect in the lyrics:

“the arc from slavery, disillusionment, and despair to readiness”.

The generalization ranges too wide. LaVette’s focus on herself, and the other female rhythm & blues singers, gives ‘Blackbird’ a feminist slant.25

In the case of ‘Blackbird’, I hope Kapurch and Smith take me to a world of hopeful, heartbroken people, who might or might not be inspired by the song, or find empathy from the lyrics and the voice.

As a fan with an attitude, I hope Kapurch and Smith distinguish convincingly between the inspiration and intentions of Paul McCartney, and interpretation by the audience and other artists.

I'll study, review, and discuss the book in the next weeks, or the next months. See you soon, and I hope to get some responses.

Hasta la vista.

rg

Appendix 1

A selection of the works by Katie Kapurch a.o. on The Beatles (updated: October 2024)

.

Perfection is not guaranteed. Suggestions about articles, books, podcasts, videocasts, radio or TV conversations are welcome.

.

- Kapurch, K. (2014). She Loves You: The Beatles, Girl Culture, and The Ed Sullivan Show. Antenna: Responses to Media and Culture, February 14. Department of Communication Arts, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Assessed October 2024: http://blog.commarts.wisc.edu/2014/02/07/she-loves-you-the-beatles-girl-culture-and-the-ed-sullivan-show/. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2016). Victorian Melodrama in the Twenty-First Century Jane Eyre, Twilight, and the Mode of Excess in Popular Girl Culture. Palgrave Macmillan. DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-58169-3.

- Womack, Kenneth, and Kapurch, K. (Eds.) (2016). New critical perspectives on The Beatles – Things we said today. DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57013-0.

- Kapurch, K., and Smith, J. M. (2016). Blackbird Singing: Paul McCartney’s Romance of Racial Harmony and Post-Racial America. In Womack, K., and Kapurch, K. (Eds.). New critical perspectives on The Beatles – Things we said today. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57013-0. pp. 51–74.

- Kapurch, K. (2016). Crying, Waiting, Hoping: The Beatles, Girl Culture, and the Melodramatic Mode. In Womack, K., and Kapurch, K. (Eds.). New critical perspectives on The Beatles – Things we said today. Palgrave Macmillan. DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57013-0. pp.199–220.

- Kapurch, K. (2017). The Wretched Life of a Lonely Heart: Sgt. Pepper’s Girls, Fandom, the Wilson Sisters, and Chrissie Hynde. In Womack, K. and Cox, Kathryn B. (Eds). The Beatles, Sgt. Pepper, and the Summer of Love. Lexington Press. pp.137– 159.

Article separately available online. Assessed October 2024: https://www.academia.edu/35277395/The_Wretched_Life_of_a_Lonely_Heart_Sgt_Peppers_Girls_Fandom_the_Wilson_Sisters_and_Chrissie_Hynde. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2018). ‘Come on to Me’ Is Paul McCartney’s Guide to #MeToo-era Flirting. Pop Matters, October 1. Assessed October 2024: https://www.popmatters.com/paul-mccartney-come-on-to-me-2608669994.html. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2018). Macca’s Jacca Revelation: More than a Sexy One Off. Culture Sonar September 25. Assessed October 2024: https://www.culturesonar.com/maccas-jacca-revelation-more-than-a-sexy-one-off/. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2019). Blac Rabbit: Turning on the Beatles Today. Culture Sonar, May 11, 2019. Assessed October 2024: https://www.culturesonar.com/blac-rabbit-turning-on-the-beatles-today/. Online.

- Kapurch, K and Smith, J. M. (2019). A Fear So Real: Film Noir's Fallen Man in Bruce Springsteen's Darkness on the Edge of Town and the David Lynch Oeuvre. Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, Volume 21, Number 1, 2019, pp. 89-108. Print. More info available at: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/725430. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2019). “She’s So Heavy” at 50: From Billy Preston to Blac Rabbit. Culture Sonar, September 27, 2019. Assessed October 2024: https://www.culturesonar.com/shes-so-heavy-at-50-from-billy-preston-to-blac-rabbit/. Online.

- Kapurch, K., and Smith, J.M. (2020). Blackbird Fly: Paul McCartney’s Legend, Billy Preston’s Gospel, and Lead Belly’s Blues. Interdisciplinary Literary Studies: A Journal of Criticism and Theory 22, no.1–2: 5–30. Assessed October 2024: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/intelitestud.22.1-2.0005. Online

- Kapurch, K., and Everett, Walter. (2020). If You Become Naked’: Sexual Honesty on the Beatles’ White Album. Rock Music Studies 7, no. 3: 209–25. Assessed October 2024: https://doi.org/10.1080/19401159.2020.1792193. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2020). 'Photograph’- We Are All Ringo Now. Culture Sonar, April 17. Assessed October 2024: Retrieved from https://www.culturesonar.com/photograph-we-are-all-ringo-now/. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2020). The Paul McCartney Song We Need Right Now. Culture Sonar, March 30. Assessed October 2024: https://www.culturesonar.com/the-paul-mccartney-song-we-need-right-now/. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2020). Astrid Kirchherr: What She Taught the Beatles. Culture Sonar, May 18. Assessed October 2024: https://www.culturesonar.com/astrid-kirchherr-what-she-taught-the-beatles/. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2020). Arising to this Moment: Bettye LaVette’s BLACKBIRDS. Culture Sonar, August 30. Assessed October 2024: https://www.culturesonar.com/arising-to-this-moment-bettye-lavettes-blackbirds/. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2020). The Beatles, Fashion, and Cultural Iconography. In Womack, K. (Editor). The Beatles in Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 247–259.

- Kapurch, K. (2021). The Beatles, Gender, and Sexuality. I Am He as You Are He as You Are Me. In Womack, K. and O’Toole, K. (Eds.), Fandom and the Beatles: The Act You’ve Known for All These Years. Oxford University Press. pp.139-166.

Article separately available online. Assessed October 2024: https://www.academia.edu/52470205/_The_Beatles_Gender_and_Sexuality_I_am_He_as_You_are_He_as_You_Are_Me_. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2021). Eat, Drink, and Get Baked with the Beatles. Culture Sonar, November 25. Retrieved from https://www.culturesonar.com/eat-drink-and-get-baked-with-the-beatles/

- Kapurch, K. (2021). Tenacious D Does the “Abbey Road” Medley. Culture Sonar, July 8 2021. Retrieved from https://www.culturesonar.com/tenacious-d-does-the-abbey-road-medley/. Online.

- Kapurch, K., Smith, J. M., & Womack, K. (2022). Rising from the Ashes: Billy Preston’s Victory. Los Angeles Sentinel, October 19, 2022. Assessed October 2024: https://lasentinel.net/rising-from-the-ashes-billy-prestons-victory.html. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2022). Unvaulting “Disney Plus Pop” in 2021: Romance, Melodrama, and Remembering in Taylor Swift’s All Too Well, McCartney’s Lyrics, and The Beatles: Get Back. AMP: American Music Perspectives, 1(2), 159–172. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5325/ampamermusipers.1.2.0159. Online.

- Kapurch, K., Mills, R., & Heyman, M. (Eds.) (2023). The Beatles and Humour: Mockers, Funny Papers, and Other Play. Bloomsbury Press.

- Kapurch, K. (2023). The Beatles and the Bard, the Walrus and the Eggman: Playing with William Shakespeare and Lewis Carroll and/as Perspective by Incongruity. In Kapurch, K., Mills, R. & Heyman, M. (Eds.). The Beatles and Humour: Mockers, Funny Papers, and Other Play. Bloomsbury Press.

- Kapurch, K., Everett, W., & Alleyne, M. (2023). Billy Preston and the Beatles Get Back: Black Music and the Wisdom of Wordplay and Wit. In Kapurch, K., Mills, R. & Heyman, M. (Eds.). The Beatles and Humour: Mockers, Funny Papers, and Other Play. Bloomsbury Press.

- Kapurch, K., & Everett, W. (2023). Come Together: Feeling the Distemper of Murk and Elation with the Beatles (1969) and with Sheila E. and Ringo Starr (2017 and 2020). In W. Moylan, L. Burns, & M. Alleyne (Eds.), Analyzing Recorded Music: Collected Perspectives on Popular Music Tracks. Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781003089926.

Article separately available online. Assessed October 2024: https://www.academia.edu/103354085/Come_Together_Feeling_the_Distemper_of_Murk_and_Elation_with_the_Beatles_1969_and_with_Sheila_E_and_Ringo_Starr_2017_2020_. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (2023). Why ‘Barbie’ and ‘The Little Mermaid’ made 2023 the dead girl summer. The Conversation, September 12, 2023. Assessed October 2024: https://theconversation.com/why-barbie-and-the-little-mermaid-made-2023-the-dead-girl-summer-210436. Online.

- Kapurch, K., and Smith, J. M. (2023). Blackbird. How Black musicians sang The Beatles into being and sang back to them ever after. The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN: 9780271095622. Paperback.

- Kapurch, K. and Smith J.M. (2024). Beyoncé’s ‘Blackbiird’ breathes new life into a symbol that has inspired centuries of Black artists, musicians and storytellers. The Conversation.com, April 3, 2024. Assessed October 2024: https://theconversation.com/beyonces-blackbiird-breathes-new-life-into-a-symbol-that-has-inspired-centuries-of-black-artists-musicians-and-storytellers-226901. Online.

- Kapurch, K. (Accepted / In Press). Sweet Dreams and Magic Feelings on Abbey Road: The Beatles’ Romance, Wives, and Gender-Bending Rock Mythos (as Revealed by Tenacious D). In Covach, J. (Ed.) (?) The Beatles’ ABBEY ROAD. Cambridge University Press.

© 2024 The Beatles Review of History. The work of the original interviewers and publishers is gratefully acknowledged and excerpts are reproduced on this site under allowances for fair use in copyright law. If anything on this blog constitutes an infringement on your copyright, please let us know, and we will consider removing the materials.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

.

Ray Charles (1958). Ray Charles @ Newport 1958. Assessed October 2024:

Kapurch, Katie, and Smith, Jon Marc (2023). Blackbird. How Black musicians sang The Beatles into being and sang back to them ever after. The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN: 9780271095622. Paperback.

Today, in late 2024, I am shelling out loads of money to fund my Beatles reading addiction, one that is quite similar to the ‘heroin’-like, sugar, fat, and mountains addictions I spend money on. Or should I say splurge? Still, I am quite selective in what I buy. I’d rather spend my Beatles money on books from Womack and Kapurch, and great stuff like ‘Teenset, teen fan magazines and rock journalism’ aka ‘Don’t Let the Name Fool You’, by Allison Bumsted and Sara Schmidt’s ‘Dear Beatle People: The Story of The Beatles North American Fan Club’, than books that mostly rehash well-known info below par, as in Luca Perasi’s ‘Paul McCartney & Wings: Band on the Run’ (2023) or ‘with The Beatles: From The Town Where They Were Born to Now and Then’ by Patrick Humphries (2024).

- Bumsted, Allison (2024). Teenset, teen fan magazines and rock journalism. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN: 978-1496853271. Paperback.

- Schmidt, Sara, and Davis, Janet (2023). Dear Beatle People: The Story of The Beatles North American Fan Club. Texas Book Publishers Association. ISBN: 978-1946182265. Paperback.

Lennon & McCartney (1968). Blackbird. On ‘The Beatles’ aka the white album (1968).

Check Katie Kapurch’s faculty profile @ Texas State University: https://faculty.txst.edu/profile/1921996.

Check Jon Marc Smith’s faculty profile @ Texas State University: https://faculty.txst.edu/profile/1922027.

Kapurch, Katie (2016). Victorian Melodrama in the Twenty-First Century Jane Eyre, Twilight, and the Mode of Excess in Popular Girl Culture. Palgrave Macmillan. DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-58169-3. Acknowledgment: p.xvi.

Assessed October 2024:

Assessed October 2024:

The official ‘I Want To Break Free’ music video. Taken from Queen - 'Greatest Video Hits 2'. Assessed October 2024:

The performance of ‘I Got a Woman’ on August 13th, 1963 on ‘Pop Go The Beatles’ outshines the more polished version of 1964, with a double-tracked Lennon voice. We hear Lennon as a rhythm guitarist at his peak. George’s typical rockabilly-inspired guitar work is still dominant in 1963. Somewhere down the line, the Beatles lost the wild rock’n’roll sound. Assessed October 2024:

Billy Preston starts a jam with The Beatles in Savile Row on January 28th, 1969 using ‘Sticks and Stones’. Assessed October 2024:

Source: Bootleg, A/B Road Complete Get Back Sessions - Jan 29th, 1969 - 3 & 4.

Kapurch, Katie, and Smith, Jon Marc (2024). Blackbird. How Black musicians sang The Beatles into being and sang back to them ever after. The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN: 9780271095622. Paperback. pp.148/9.

Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. Henry Holt & Co. ISBN: 9780805052480. Hardcover.

McCartney, Paul and Muldoon, Paul (editor) (2021). McCartney – The Lyrics, 1956 to the present. Allen Lane. ISBN: 978-0-241-51933-2. Hardcover.

McCartney, Paul (author) and Mitchell, Adrian (editor) (2001). Blackbird Singing: Poems and Lyrics 1965-1999. Faber & Faber Ltd. ISBN: 0-571-20992-0. Paperback.

‘McCartney: A Life in Lyrics’. An iHeartpodcast and Pushkin Industries production. 24 Episodes in 2023/2024. Assessed October 2024:

Lennon said in 1970: “I thought it was interesting that Nina Simone did a sort of answer to ‘Revolution’. That was very good – it was sort of like ‘Revolution’, but not quite.” Nina sang from the position of the oppressed.

“The only way that we can stand, in fact

Is when you get your foot off our back. Get off our backs, get back…

Nina Simone made clear what the revolution was going to be about:

“And now we got a revolution … Yeah, your Constitution / Well, my friend, it's gonna have to bend / I'm here to tell you 'bout destruction / Of all the evil that will have to end.”

Nina Simone addressed openly how she would be perceived as being violent and not just friendly

“I know, they'll say I'm preachin' hate”,

as the white middle-class and the (economic, political, and military) elites, just like Lennon who believed violence is not an effective means to get the people (voters) behind you. Simone and Lennon seem to agree that the oppressor also “Well, you know you got to clean your brain”. Violence alone is not enough.

Sources:

Wenner, Jann, and Lennon, John, and Ono, Yoko (1971). The Rolling Stone Interview: John Lennon. Part Two – Life With The Lions. Rolling Stone, February 4, 1971. Assessed April 2021: https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/lennon-remembers-part-two-187100/ and http://www.johnlennon.com/music/interviews/rolling-stone-interview-1970/. Online.

Assessed October 2024:

LaVette, Bettye and David Ritz (2012). A Woman Like Me. Blue Rider Press (Penguin Group). ISBN: 978-1-101-60067-2. eBook.

Bettye LaVette performing ‘Blackbird’ at Farm Aid in 2021. Assessed October 2024:

Sheffield, Rob (2024). This moment to arise: the revisionary genius of Beyoncé’s ‘Blackbird’. Rolling Stone, March 29, 2024. Assessed October 2024: https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/beatles-beyonce-blackbird-1234996099/. Online.

Sheffield, Rob (2017). Dreaming The Beatles. HarperCollins Publisher. ISBN: 9780062207678. e-Book.

A nostalgic orientation does not intend to be appreciative. Some nostalgia-oriented magazines are like the next-door neighbor’s cat, going through their second, third, or seventh life. They offer good stuff from the past, but the sales numbers do come from rehashing old stuff. Representatives of the branch are: Rolling Stone, Uncut, Mojo, etc.

Bettye LaVette (2020). Blackbirds. Assessed October 2024: