Studying ‘Blackbird’ is like walking into a portal to learn about a past that doesn’t belong to me, and step into real-life events that flow through me.

This new episode took me a little longer. A small protestant bird in the back of my head sings: ‘you are busy doing nothing’. Well, could be.

1.

150km walking and running in eight days a week.

.

2.

watching, listening, and reading about the post-election upheaval in the US. Incompetent machos, women abusers, and pro-Russia agitators are nominated for prominent government positions. All around the world political folks flock toward Chinese leadership for influence, support, and stability.

.

3.

There were fierce crazy fights in the streets in Amsterdam. Maccabi-asshole-fans from Israel prowled the city, acting like provocative scum against Amsterdam citizens. Thin-skinned cab drivers from Amsterdam took justice into their own hands. Next ill-fated young kids get excited, lose impulse control, and chase people on their scooters. You can blame these rascals. I suggest checking out their parents, teachers, and imams, who refuse or are unable to provide information, education, and training for these kids to succeed in school as the portal to a racist anti-immigrant culture and economy that depends on low-cost immigrants. This failure should not come as a surprise in a capitalist society. Values, norms, and culture are frozen by conservative whities, with a racist almost Calvinistic-like attitude.

On top of it all, politicians weave their narration in a way GOP and Trumpians do all the time.

Too many people reaching for a piece of cake

Too many people pulled and pushed around

Too many people preaching practices

Too many people are angry or scared.

.

4.

Reading, reviewing, and experiencing a book like ‘Blackbird’, fires up, and invites me to study other sources. A friend at the International Institute of Social History gets me a copy of the W. E. B. Du Bois Lectures, Stuart Hall delivered at Harvard University in April 1994.1An eye-opener. The text of forces me to rethink much of what I believe about race. A librarian advises me to study the history of the concept of race: ‘Who’s Black and Why? A Hidden Chapter from the Eighteenth-Century Invention of Race'.2

Inquiries at universities in Amsterdam led me to ‘The cultural memory of Africa in African American and Black British fiction, 1970-2000’ (2016), an anthology edited by Leila Kamali.3 The essays cover topics Kapurch and Smith address in ‘Blackbird’. It includes a major piece on Toni Morrison’s novel ‘Song of Solomon’.4 Morrison uses African American folktales, including the Blackbird Flying Myth. Unforgettable.

From the public library, I borrow a copy of 'You Don’t Know Us Negroes, and other Essays’, by Zora Neale Hurston.5 Now that’s a literary achievement, entertaining, informative, and triggering emotions.

Thank you for the inspiration, Katie Kapurch and Jon Marc Smith. There is a lot to study. A few times this week, I was locked in reading, as the city woke up. I heard early morning noises: a lonely man on his scooter on his way to work. A young woman on a bike, talking too loudly on the phone. Early deliveries to the shops down below in the street. Once I noticed a new day dawning when I heard the quietness of the calm still night air change into a breath of wind. It was time to go to sleep.

.

5.

One of the greatest gifts this week is Joe Boyd’s magnum opus ‘And the Roots of Rhythm Remain’6 getting the attention it deserves. The remainder of this paragraph is based on the discussion of the book with Joe Boyd in Rock’s Backpages podcast.7 For our exploration of ‘Blackbird’, it is relevant to get an understanding and feel for the destructiveness aimed at joy, laughter, and rhythm, undermining the music, by the slave owners in the Americas, and the South African protestant Dutch settlers:

“A Xhosa expression for conversion to Christianity was to give up dancing”

“... the new Protestant churches were (...) hectoring the faithful about their transgressions and placing music and dance near the top of a list of sins.”

Salafist mullahs appear in the book as “music-banning villains”,

It is not only them.

Throughout history, Christianity hasn’t been much different:

“Barbara Ehrenreich’s ‘Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy’8 gives chapter and verse on the church’s obsession with preventing women from moving their bodies; the headscarf, for example, was introduced to keep their hair from swaying during services. (...) John Calvin warned that ‘venom and corruption are distilled to the very depths of the heart by melody’.”

The Guardian introduces Joe Boyd’s ‘And the Roots of Rhythm Remain’ as9:

“The producer’s epic account of global music’s cross-pollination is an inspiring tale of seduction, expression and freedom from oppression.”

The conversation in the ‘Rock’s Backpages’ podcast about the destructive colonial power of the Dutch as an example of this oppression is spot on. Even today, the majority of the conservative Dutch hate the multicultural variation.

The Dutch settlers in South Africa (The Boers) were the equivalent of the ultra-puritanical Protestants who settled in North America from Britain. The Boers’ version of Protestantism was unbelievably hard-core NO-Joy. These settlers took over a country full of people whose specialty is joy through music.

Hugh Masekela:

“The government despised our joy. They couldn’t figure out how Africans could still find any pleasure under such harsh social conditions.”10

A couple of decades later, Malcolm McLaren and Trevor Horn go to South Africa to record some music11 with local black musicians, and they were also surprised: “It was a frightening experience. That song is about the road to Soweto. Those people were like the song, chirpy and optimistic despite the horrible circumstances.”12 The whites in Europe and the Americas would benefit from learning to be happy while in existential turmoil.

Meet dat Hypocrite on de street,

First thing he do is to show his teeth.

Nex’ thing he do is to tell a lie,

An’ de bes’ thing to do is to pass him by.13

The Boers set up the urban life for Black Africans, to be as intolerable as possible, so the people would not stay in the city. They wanted them to work just for a season, and then move on. As the economy grew, Malay slaves were imported from the Dutch East Indies (current Indonesia). Lascivious behavior among settlers, sailors, Malays, and local Khoikhoi (the Hottentots) turned Cape Town into a ‘Sodom’ of interracial couples and their offspring, who, centuries later, would constitute a third classification under apartheid, the ‘Cape Coloureds’. As people and cultures blended, the mix became larger, richer, and more varied. Everybody was mixing, you couldn’t tell what people were on the scale of black to white. In the cities, controlled by the Boers, you couldn’t get a good cup of coffee, but around the cities, where millions of Blacks showed no signs of leaving, there was entertainment, good food, great coffee, and lots of music. They were worldly people, they were hip. Racial integration and music as a source of joy were intolerable for the Dutch settlers. For the Boers authority must be obeyed, democracy is against God, evolution is a lie, and music is sinful. The Boers freaked out, and got the hell out of Cape Town, up the coast and inland, also because The Brits came in. For them, it was the paranoia blues.

Today, most Africans, Europeans, and North Americans see

“music is an expression of the human world – our aspirations, tribulations and celebrations”. [9]

’And the Roots of Rhythm Remain’ is a history told through music. A book of almost a thousand pages in a light tone is quite a feat. Joe Boyd is a great storyteller. I am excited about the forthcoming audio version and the playlists to illustrate the narration.

.

6.

Every day, I read a couple of African American folktales (short stories) to get a feel for the magic, and the storytelling. I have a friend who descended from African Suriname roots. When I visit, I read these stories to her little girl.14

7.

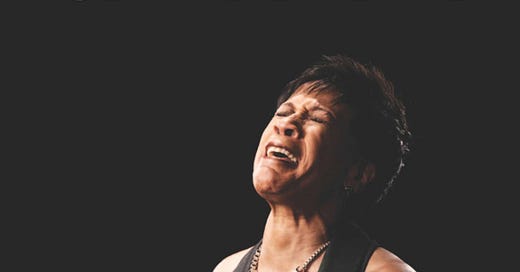

Listening to Bettye Lavette’s music and reading her autobiography ‘A Woman Like Me’15 is fun.

The story struck me like lightning in my head. I was floored.

You don’t mess with her Bettye LaVette. She is a hoochie-coochie gal, but not a badass in hell. You should love and appreciate her. If Jesse James had been a gorgeous good-looking sexy guy, he might have kept the guns close to the bed when making love, but he sure got to use his lips and tongue to pleasure her.16

The story of Betty Jo Haskins, aka Bettye LaVette, and the extraordinarily talented editor/storyteller David Ritz creates a world my middle-class white European mind can’t feel or understand. The tales LaVette sings in her songs convince me that I get a glimpse of a life out of my bounds. Her oeuvre makes sense now. I am ecstatic.

This book excites me, like the books of explorers from the 19th and early 20th centuries. At first, the scene in the ‘Prologue’ seems fiction, but it makes perfect sense another fifty pages later.

“A vicious pimp was precariously holding on to my right foot as he dangled me from the top of a twenty-story apartment building at Amsterdam and Seventy-eighth Street. (...) he was sadistic, callous, and impossibly gorgeous. (...) I am a woman who does not like admitting mediocrity at any task—particularly one where fucking is the centerpiece. Yet in all honesty, I cannot claim the status of a world-class whore. I tried but stumbled. (...)

I knew the man was monstrous, but I did not see him as a murderer. Of course, I couldn’t be sure, but I had to take that chance.

“If you think I’m worth the rest of your life in jail, then drop me.”

“Fuck you,” he said. “You’ll never make it without me.'

That’s when he pulled me up, slapped me around, and told me to get out. I ran like the wind, leaving everything behind.

I hit the streets of Manhattan wearing a pair of shorts, a bra, and no shoes. I had no money.

Where was I supposed to go?

What was I supposed to do?”

After finishing ‘A Woman Like Me’, canceling artists or art, for whatever reason, seems ridiculous to me.

It is not up to whities and people living safe, boring lives to diminish the suffering of Black women by looking at it from a multicultural perspective, as Bettye LaVette does:

“When I fell into the Detroit music scene, I didn’t know any men who weren’t making money off women. Whether the women were actually whores or ladies singing soul songs in the studio made little difference. Men were running women. This is the situation I accepted, even embraced. This was the reality I worked with. I liked many of these pimp-producers. I liked the edgy life they led. They were exciting, unpredictable, and sharp in mind and dress. When they had money, they let you know it by the cars they drove and the clothes they wore. When they didn’t have money, they found a way to keep steppin’ and stylin’ all the same. They were survivors who taught me to survive. I don’t mean that there weren’t serious assholes among them, but every culture has its assholes. In this culture, they were my men and I was their woman.”

Take this, dear reader,

about the entertainment industry in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, and the position of women only a few decades ago in our part of the world.

May it serve you well:

“Tammi Montgomery (Tammi Terrell, the singer who) wound her voice around Marvin’s on those beautiful duets, and Yvonne Fair had much in common. They were singers who had both been with James Brown, onstage and in bed. Like me, they loved being around singing stars and pimp-producers to whom they gave up their love easily and often. We were essentially groupies who sang. (...)

The notion of the groupie/singer helps explain why Tammi, Yvonne, and I did the things we did. Diane Ross undoubtedly also fits into that category. Even though we were semi-stars ourselves, we were so enamored of the stars that we’d use every feminine charm at our command to win our way into their world. Beyond the sheer delight of being in the company of magnificent artists like Marvin Gaye or David Ruffin, we knew that we needed to be more than good singers. We needed men to sponsor our cause. We knew that they liked hearing us sing. But we also knew that if they enjoyed sex with us, they’d help our careers.

A word about physical violence.

I realize it’s politically incorrect to admit this, but the sight of a man slapping a woman did not horrify me.

Context is everything. In the context of the Detroit showbiz culture of the sixties, men slapped their women around. They just did. It may sound radical to say so, but some women needed that. Some women even benefited from that. We all knew—we saw it with our own eyes—that Ted was slapping Aretha around. But without Ted’s grooming, Aretha would never have been a superstar.

Same with Ike and Tina. I hated how Hollywood pictured Ike as a sadistic ogre. There was much more to the man than the movie revealed. Without Ike, there would be no Tina. He created her, reshaping her to become another person. Offstage he called her Ann. Onstage she was Tina. Through her long years with Ike, hundreds of men wanted Tina. Hundreds of men would have whisked her off in a hot minute. Tina could have left Ike at will. She chose to stay because she wanted to learn the lessons he had to teach. And those lessons resulted in her becoming a millionaire many times over. (...)

As you can see, I’m a man’s woman.

(...) Men had a stranglehold on the industry that interested me most.

Women were their props.

The only question was what kind of prop was I going to be.”

Whatever fans or scholars are suggesting about the connection The Beatles had with Black culture and their music. I am convinced these white English boys from Liverpool did not have a fix on the lives of the blacks in America and how slavery, white hate, institutionalized racism, poverty, and the music business helped to create the music they loved.

rg

© 2024 The Beatles Review of History. The work of the original interviewers and publishers is gratefully acknowledged, and excerpts are reproduced on this site under allowances for fair use in copyright law. If anything on this blog constitutes an infringement on your copyright, please let us know, and we will consider removing the materials.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Hall, Stuart; edited by Kobena Mercer; Foreword by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (2017). The Fateful Triangle - Race, Ethnicity, Nation. Harvard University Press. ISBN: 978-0-674-98300-7. e-book.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis, and Curran, Andrew S (editors) (2022). Who’s Black and Why? A Hidden Chapter from the Eighteenth-Century Invention of Race. Harvard University Press. ISBN: 978-0-674-27612-3. e-book.

Kamali, Leila (editor) (2016). The cultural memory of Africa in African American and Black British fiction, 1970-2000. Palgrave-MacMillan. ISBN: 978-1-137-58171-6. DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-58171-6_3. e-book.

Morrison, Toni (1977/2004). Song of Solomon. Vintage International. ISBN: 978-0-307-38812-4. e-book.

Hurston, Zora Neale, and Genevieve West and Henry Louis Gates Jr. (editors and Introduction) (2022). You Don’t Know Us Negroes, and other Essays. Harper Collins. ISBN: 978-0-06-304387-9. e-book.

Boyd, Joe (2024). And the Roots of Rhythm Remain. A journey through global music. Faber & Faber. ISBN: 978–0–571–36002–4. Print.

Rock’s Backpages podcast (2024) Episode 184: Joe Boyd on global music + Kate & Anna McGarrigle. Rock’s Backpages, 2 September 2024. Assessed October 2024: https://megaphone.link/PAN1993957891. Online.

Ehrenreich, Barbara (2006/2011). Dancing in the Streets A History of Collective Joy. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN: 9781429904650. e-book. Chapter 4: ‘From the Churches to the Streets: The Creation of Carnival.’

Vulliamy, Ed (2024). And the Roots of Rhythm Remain: A Journey Through Global Music by Joe Boyd review – the Proust of music. The Guardian, 19 August 2024. Assessed November 2024: https://www.theguardian.com/books/article/2024/aug/19/and-the-roots-of-rhythm-remain-a-journey-through-global-music-by-joe-boyd-review-the-proust-of-music. Online.

Masekela, Hugh and Cheers, D. Michael (2004). Still Grazing: The Musical Journey of Hugh Masekela. Three Rivers Press. ISBN: 978-0609609576. p. 70.

McLaren, Malcolm (1983). Soweto. Produced by Trevor Horn. Composed by Malcolm McLaren and Trevor Horn. Virgin Records. Assessed November 2024:

Savage, Jon (2010). Jon Savage on song: Malcolm McLaren – Soweto. The Guardian, 26 April 2010. Assessed November 2024: https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2010/apr/26/jon-savage-malcolm-mclaren-soweto. Online.

‘Now Let Me Fly’. Source:

- Hughes, Langston, and Arna Bontemps (editors) (1958). The Book of Negro Folklore. Dodd Mead. ISBN: 9780396041573. Paperback. pp. 301.

Abrahams, Roger D. (editor) (1985/1999). African American Folktales: Stories from Black Traditions in the New World. The Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library. Phanteon Books. ISBN: 978-0-307-80318-4. e-book.

Abrahams, Roger D. (1983). African Folktales. Traditional Stories of the Black World. Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library. Phanteon Books. ISBN: 978-0-307-80319-1. e-book.

Gates jr., Henry Louise, and Tatar, Maria (2018). The Annotated African American Folktales. Liveright Publishing / W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN: '978-0-87140-756-6. e-book.

Hamilton, Virginia (text) and Dillon, Leo and Diane (illustrations) (1985/2004). The People Could Fly, the picture book. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN: 978-0-553-50781-2. eBook.

LaVette, Bettye and David Ritz (2012). A Woman Like Me. Blue Rider Press (Penguin Group). ISBN: 978-1-101-60067-2. e-book.

Did I make this up?